Goodbye, Fall Semester!

Wrapping up a semester filled with exciting research, computer models, and...econophysics?

Oh boy! It’s been a whirlwind semester. Below is just some of the stuff we’ve been up to at Simpson Physics+Engineering for the past few months.

Capstone Continuation

Seniors continued their capstone projects working on everything from aerodynamics to minigolf courses to retrofitted Millennium Falcon radars. Kayla Jensen, one of our top seniors, finished her time at Simpson researching a capstone project I’ve been interested in for a long time. Do you know the coin pusher machines in arcades and casinos? The ones with hundreds of precariously perched coins teetering on the edge, tantalizing you at the prospect that one more coin will trigger a cascade, spilling riches into the tray, and sending you home a wealthier person?

Do those coins ever topple? If they do, is it only a few at a time, or is it a gushing avalanche?

What Kayla discovered is that the coin pusher is a great candidate for what physicists call self-organized criticality. This idea was developed in the late 1980s by Per Bak and collaborators as a way to describe systems that naturally evolve to a critical state without fine-tuning. In these systems, small disturbances—like one more coin deposited in a coin pusher—can lead to responses of all sizes. Most changes are tiny (just a few coins), but occasionally a small nudge triggers a large event (an avalanche of coins). The hallmark signatures are power law distributions, scale invariance, and a kind of universality where very different systems share the same statistical behavior. Earthquakes are the classic example. Most are small, a few are catastrophic, and there is no single characteristic size.1 The same mathematical structure shows up in sand piles, forest fires, neural activity, and financial markets.

If it could be applied to the coin pusher, this framework gives clear answers to the questions above. Most coins fall individually or not at all, but once the machine reaches a critical configuration, it becomes possible for a single added coin to trigger a cascade involving many others. There is no typical avalanche size. Small and large events coexist, and their probabilities follow a power law rather than a bell curve.

Kayla began by building a Python simulation of rigid-body coins being pushed forward incrementally (see above). That model was visually satisfying but computationally heavy. She then made a conceptual leap to a cellular automaton inspired by the Bak-Tang-Wiesenfeld sandpile model. With that simpler model, the underlying physics snapped into focus with a power law distribution of avalanche sizes characteristic of self-organized critical phenomena, along with scale invariance and critical exponents that appeared to be in the same universality class as Bak’s original sandpile model.

Congratulations to Kayla for great work on the capstone and throughout her physics career at Simpson!

Becoming Computer Modeling Leaders

Kayla was not alone in her modeling efforts. Part of my goal is to transform Simpson into a leader in mathematical and computer modeling. It wasn’t long ago that Simpson led the nation competing in COMAP’s Mathematical & Interdisciplinary Competition in Modeling, the “Olympics of math modeling competitions.”2

For the 10th year in a row, Simpson fielded more teams than any other college or university in the U.S. In the ICM competition, 22 teams represented the United States. Ten were from Simpson, located in Indianola.

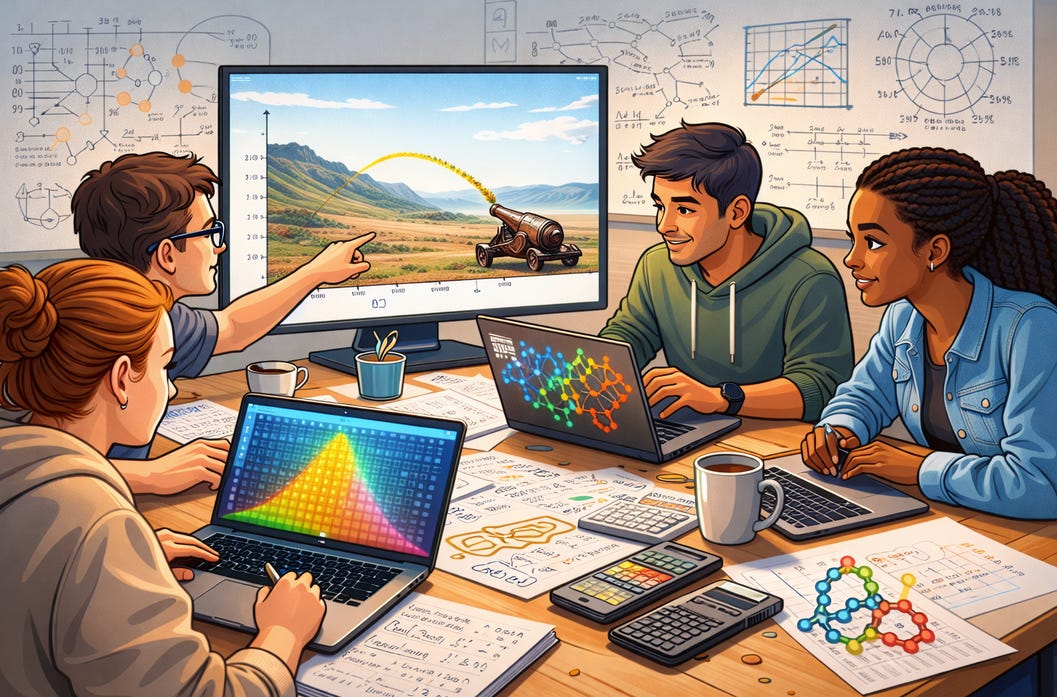

Toward that end, this fall, we had 15 students compete in the University Physics Competition (UPC). The UPC is a worldwide, 48-hour team contest held every November in which groups of undergraduates tackle a real-world physics scenario and write a formal paper applying physical principles to solve it. Students work in teams of three and must analyze, model, and interpret their chosen problem under a tight time constraint, just like practicing scientists and engineers do.

All of our teams chose the Artillery problem, which asks students to (1) model the firing of a historical cannon to hit a target roughly 1,200 meters away and (2) generalize that solution across a range of distances, elevations, and environmental conditions. Unlike textbook projectile motion problems, the Artillery problem deals with the messy realities of drag, wind, and limited computer access. Students were specifically asked to design a method that a mathematically trained artillery officer from the 1800s could use (i.e., something that couldn’t use modern computers). Teams combined analytical mechanics, numerical modeling, and careful approximation to build a practical, defensible model under intense time pressure.

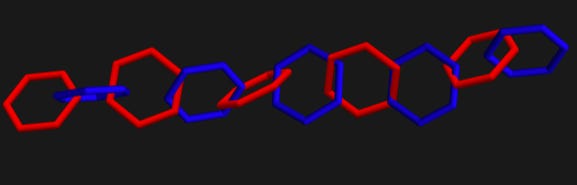

In addition to UPC, I’ve made it my mission to incorporate computational modeling throughout our curriculum. This fall, my Thermal Physics course wrapped up with a final project modeling the behavior of polycatenanes. A polycatenane is a hypothetical material made not of chemically bonded chains, but of many molecular rings mechanically linked together like molecular chain mail.

The idea of polycatenanes has been around for decades, but large, bulk polycatenanes remain theoretical. This raises many interesting questions: Given the chain structure, would polycatenanes be super stretchy? Would they flow like a liquid or behave like a solid? Since the rings aren’t technically connected, would they still transmit heat or would they behave like a super thermal insulator? We can use physical laws and computer simulations to answer these questions, even though polycatenanes haven’t been invented yet.

Students used Monte Carlo simulations to explore how polycatenanes behave. Using simple statistical rules, they tracked quantities like energy, length, and forces to begin mapping out a phase diagram. The project forced students to apply what they learned in class to make strong theoretical predictions that they could justify with mathematics and logic.

Understanding and Communicating Science

One of our goals is that all Simpson physics graduates should be able to read, understand, and communicate the latest scientific research. Toward that end, we require students to take a seminar class in which they choose an active physics research area and explore it in depth by reading peer-reviewed papers, not textbooks. This year’s topic was, somewhat to my surprise, econophysics.

Econophysics is exactly what it sounds like. It’s the application of tools from statistical physics, nonlinear dynamics, and complex systems to economic systems. Instead of gas molecules or magnetic spins, the “particles” are people, firms, or trades. Instead of temperature or pressure, you study volatility, correlations, and risk. The math and computational techniques are familiar to physicists, even if the system under study looks very different at first glance.

It’s fair to ask whether econophysics is really physics. The answer is a firm yes. Economies are just as physical as magnets and gases, albeit with many more particles and vastly more complex interactions. Many of the core ideas in econophysics come straight out of statistical mechanics, random walks, diffusion, and scaling laws. Physicists were drawn to these problems in part because economic data sets are large, messy, and real, exactly the kind of systems where traditional equilibrium assumptions break down and statistical approaches shine. There’s also a practical reason:

Over the past few decades, physicists have been heavily recruited into finance, data science, and quantitative analysis roles, where the same skills used to model complex physical systems translate directly to markets and risk modeling. These jobs generally pay very well (easily in the low six figures). Entire subfields of quantitative finance are dominated by people trained as physicists, not economists. This year’s seminar made that connection explicit. Students saw firsthand that a physics degree is not training you for a single narrow career, but rather how to model complicated systems, analyze data, write code, and make sense of uncertainty—skills that are valued across many fields. Econophysics just happens to be a particularly vivid example of how far those skills can carry you.

Students did great work diving into the topic, learning entirely new vocabulary, and applying the physics principles they learned in classes to entirely new phenomena. For their final projects, students needed to effectively communicate the specific research topic they explored. Final topics included things like:

How Thermodynamics Models Predict Wealth Inequality

Phase Transitions & Collective Behavior in Markets

Market Bubbles and Crashes

Fractional Calculus and Market Dynamics

Network Theory & Risk Propagation in Financial Markets

Lastly, while it’s important to communicate technical information to other scientists, that’s not enough for a scientist to succeed in the 21st century. To receive public support and funding, scientists must be adept at communicating to lay audiences. This includes communicating on social media platforms like podcasts, Twitter, and TikTok. To expose students to this different style of communication, we experimented by having them present in the style of these different platforms. Students showcased their creativity in these assignments. Examples include everything from Will Bacus’s Family Guy-inspired TikToks on econophysics measurements of inequality…

to Chris Duane and Ethan Sipos’s Robe Talk podcast:

Overall, this semester was a reminder of what physics education can be at its best: curious students tackling unfamiliar problems, building models from first principles, running experiments to test hypotheses, and learning how to communicate complex ideas clearly. From coin pushers to markets to hypothetical materials, our students showed that physics is not just a body of knowledge, but a way of discovering how the world works.

About the Author:

Aaron Santos is an innovator, author, and physicist. He’s written two books, How Many Licks? Or, How to Estimate Damn Near Anything and Ballparking: Practical Math for Impractical Sports Questions, which teach the art of estimation in fun and irreverent ways. He founded two nanoscience companies and is currently writing his third book, which explores the history, science, and future of nanotechnology. You can follow him on BlueSky.

Know someone who would be a good fit for Physics+Engineering@Simpson? Let me know! Don’t forget to subscribe, share, and leave a comment!

Fun fact: Guttenberg-Richter scaling is an example of a power law. Power laws are scale free, meaning the average size of an earthquake according to the GR scale is infinite.

Staff, Compiled Register. “Simpson Students Excel in Math Competition.” The Des Moines Register, DES, 27 Apr. 2014, www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/education/2014/04/27/simpson-students-excel-math-competition/8189691/. Accessed 29 Dec. 2025.